Imagine a place where you are accused of a crime. Where you can lose your liberty. Where you can lose your job. Where you can lose everything you have worked so very hard for.

Imagine that during this trial, the Government only introduced a single piece of paper that reads “You’re Guilty”. That’s it.

Imagine during that trial, you have no way of challenging or questioning that single piece of paper. That is it. You are guilty.

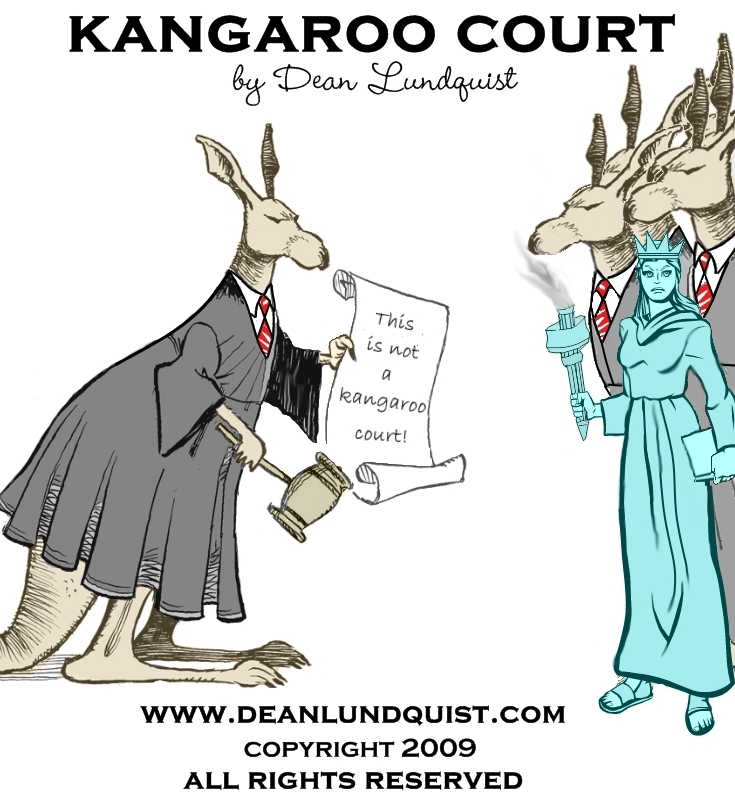

Where is that place???

Iraq? Afghanistan? China? North Korea?

It was actually, here, in the good old United States. That was until last week. That is exactly what happened all across the United States and even in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

But, you say, we have The United States Bill of Rights and the Sixth Amendment which reads:

In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the State and district where in the crime shall have been committed, which district shall have been previously ascertained by law, and to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the Assistance of Counsel for his defence.

It used to be that the Government would simply enter the breath test result or the blood lab result with no live witnesses. One piece of paper. They would enter that one piece of paper and you were done. You cannot cross-examine a single piece of paper. It cannot speak back. It cannot answer questions. So, you were left with a magic number and no means to challenge it.

Last week, the United States Supreme Court came down with a landmark decision entitled Melendez-Diaz v. Massachusetts. This case confirmed the accused’s land standing, but sequentially eroded Confrontation Right inherent in the Sixth Amendment of the United States Constituion.

Now the Government will have to provide for a live witness if they want to introduce into Court any form of forensic science or analysis result.

MELENDEZ-DIAZ SUMMARY

The Sixth Amendment of the Constitution guarantees each individual the right to confront any witness brought against him or her. This right is a fundamental right and as such must be guarded heavily. This right to Confront extends to and includes the “use” of an affidavit which is defined as a declaration of facts written down and sworn to by the declarant before an official authorized to administer oaths. (Black’s Legal Dictionary) It has also been defined by the highest court in the land as a solemn declaration or affirmation made for the purpose of establishing or proving some fact. (Crawford) (emphasis added). Upon reviewing the “certificates” presented by the prosecution in the case against the defendant, the Davis court determined that said certificates were the functional equivalent of live, in court testimony, as it does precisely what a witness does during direct examination, establishes or proves a certain fact.

In the specific case against Melendez-Diaz the government and the dissent raised a number of arguments, all of which the Majority opinion was able to successfully thwart by reviewing previous case law on the issue. The first argument raised was that analysts were not “accusatory” witnesses. The Court, using a strict interpretation of the Constitution, held that it was not that an individual is accusatory which demands confrontation, but instead it is that the witness is being brought “against” the defendant. In order to testify “against” someone an individual provides testimony against the defendant by proving one fact which is necessary for conviction. Furthermore, the Court outlined two (2), and only two (2), classifications of witnesses: there are those that are used against the witness, which must be produced according to the Confrontation Clause, and those that are in favor of the defendant, which the defendant may chose to call pursuant to Compulsory Process. There is no classification for “accusatory witnesses”

The second argument raised was that analysts are not “conventional” witnesses as they did not perceive the actual crime created nor did they observe any human action related to said criminal activity. The Court, however, was not convinced in this reasoning as it would exempt all expert testimony from the Confrontation Clause since most expert witnesses have neither witnessed the crime or any human action related to the crime. Furthermore, the Court went on to analogize an individual who is asked by the police to write down what he or she saw to a request made by the police to analyze an object and to interpret what said test results reveal; both of which are similar and should be treated similarly.

The third argument was that there was a significant difference between testimony which recounts a historical event and testimony in regards to neutral, scientific evidence. This argument, however, was too similar to the reasoning in Ohio v. Roberts, in regards to the indicia of reliability, which was overturned in Crawford. The Court noted that there are a number of reasons why the reliability of the test must withstand the cross examination process. These reasons highlighted in particular the fact that the majority of laboratories for forensic evidence are administered by a law enforcement agency and reports from said laboratories must frequently be submitted to the head of the agency which can lead to pressure or incentives to alter evidence in a manner favorable to the prosecution. In addition, the Court likened an analyst who falsified a lab report to a witness who fabricated his or her story when providing information to the police and stated that the fear of cross examination will act as a deterrent in the offering of such false reports. Finally, the Court analogized a forensic analyst to an expert witness who is asked to render his or her opinion. Without the ability to cross examine neither the analyst’s, nor the expert’s training, or lack thereof, will be highlighted for the jury and the jury will, therefore, be missing a crucial fact to weigh the expert’s or analyst’s credibility.

Another argument raised was that the analyst’s report is a business record and as such can be admissible regardless of hearsay issues. This argument, like the above mentioned arguments, is also fatally flawed as the Court in Palmer v. Hoffman expressly stated that even where a report is created in the regular course of business, if said report is also the production of evidence for the use of trial the Confrontation Clause will apply. The Court in Melendez-Diaz used this case and stated specifically that an analyst report, while possibly a business record, will always be prepared for use essentially in court and as such is bound to the requirements of the Confrontation Clause. The very nature of the business records exception is that the report is created for the administration of the entity’s affairs and not for the proving or establishing some fact, this fact alone is what makes said documents not testimonial. Where, however, it is prepared for the possibility of being used at trial it makes that same report testimonial in nature and therefore subject to the Confrontation Clause.

The next argument is that a defendant can easily subpoena the analyst to appear at trial. This argument, however, overlooks the fundamental principle that the prosecution has the burden of presenting its witnesses and that it is not the defendant’s burden to bring any adverse witnesses into trial. Moreover, just because a defendant has the ability to subpoena an individual does not guarantee that that individual will agree to testify or even appear at trial further highlighting the need for the prosecution to bring forth any witness against the defendant.

The final argument brought forward is that by requiring analysts to testify, the court will be run less efficiently and trials will drag on. The Court does not agree with this assumption, however, as there are a number of states which have their own statutory provisions requiring analysts to be present in court when the report is entered into evidence and such inefficiency has not yet been noticed. The Court further stated that inefficiency, alone, will never defeat or overcome a Constitutional right. While a defendant will always have the burden to raise a Confrontation Clause claim, there may still be limitations on raising that claim which include a notice-and-demand requirement which some states have already created. This requirement will place a timing limitation on when such claims can be raised and the Melendez-Diaz court has expressly stated that the simple notice-and-demand requirement is constitutional as it has not revoked the defendant’s right to making said claim, it only places a limit on when that claim can be made. Finally, the Court noted that it will be highly unlikely for defense attorneys to insist on live testimony which will only highlight, rather than cast doubt on forensics, and that defense counsel will only demand the presence of an analyst when the procedures used or other similar issue is present in the case at hand thereby removing the concern over inefficiency from concern.

One response to “Piece of Paper Reads: “You’re Guilty”. Well Not Any More.”