It is true. They say beauty is in the eye of the beholder. Every year they have the world’s ugliest dog contest where invariably the reporters report on this event and blast the picture of the world’s ugliest dog all over the internet. Invariably comments come from all across the world that the dog isn’t ugly but it is in fact quite handsome or pretty or overall beautiful in its subjective ugliness. In the subjective world of attraction and visual esthetics, it is true that beauty is in the eye of the beholder.

It is true. They say beauty is in the eye of the beholder. Every year they have the world’s ugliest dog contest where invariably the reporters report on this event and blast the picture of the world’s ugliest dog all over the internet. Invariably comments come from all across the world that the dog isn’t ugly but it is in fact quite handsome or pretty or overall beautiful in its subjective ugliness. In the subjective world of attraction and visual esthetics, it is true that beauty is in the eye of the beholder.

However, in the scientific world, in the analytical chemistry world beauty is not in the eye of the beholder. Beauty is not a fungible concept in chromatography. It is empirical. The basic fundamentals of gas chromatography hold that in chromatography and when a flame ionization detector is used, in the resulting chromatogram we want and we demand tall, skinny peaks that are symmetrical in nature and are sufficiently removed from one another so as to create a gap otherwise known as resolution between peaks.

The concept of the tall, skinny peak that has resolution or distance between the different peaks and is symmetrical in nature is the key fundamental characteristic of chromatography. A chromatogram that does not have tall, skinny peaks that are symmetrical in nature and are sufficiently removed from one another so as to create proper resolution between peaks is indicative of an improperly performing analytical device. In other words, “it ain’t working good”.

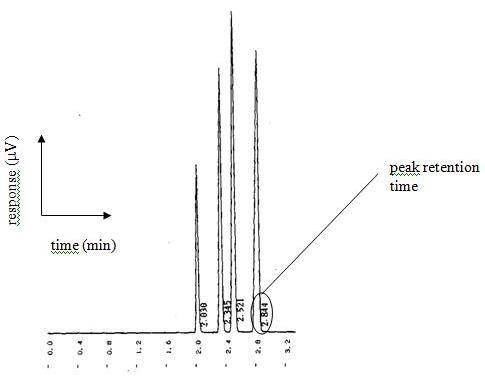

One of the problems that can manifest itself when we do not have tall, skinny peaks that are symmetrical in nature and are sufficiently removed from one another so as to create proper resolution between peaks is called co-elution. Sometimes it is very easy to spot in the chromatogram as depicted below.

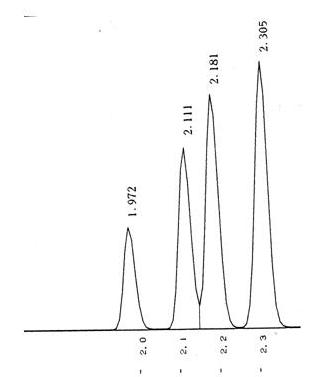

Sometimes it is not so easy to detect as shown below.

Co-elution is a particular problem to gas chromatography wherein a molecule or an analyte of similar or near similar relative retention time elutes or comes out of the column into the detector such as the flame ionization detector at or around the same time as the targeted analyte of interest. This can cause a problem with respect to the quantification and also the qualitative aspects of the test itself. Qualitatively when one has a co-elution event, it is a mark of poor chromatography and that the analytes are not separated sufficiently between one another and therefore cannot be distinguished necessarily one from the other. As we have discussed previously, it is the area under the peak that is the measurement when compared against the calibration curve that results in the quantification of the measurement on the particular detector. In that a co-elution event occurs, where there is shared area under the peaks, it is important to know the way the analytical device attempts to correct for this event. It may not even recognize that it is two separate analytes and may not correct at all. However, in that there is insufficient separation between the different peaks, even with the possible programs attempting correction, one can never be certain what contribution the co-eluding peak has to the measurement of the analyte of interest in reality. This is why we want the tall skinny peaks that are more or less symmetrical and sufficiently separated so this problem doesn’t occur.

Another form of problem in gas chromatography, especially with a flame ionization detector being used, is what is called elevated baseline error or baseline drift.

Elevated baseline error or baseline drift is the gap that is noticeable in the chromatogram that occurs after the peak where the line does not return to the accepted baseline. Again as previously mentioned it is the area under the peak that provides the quantification and therefore it can inflate the reported BAC result.

Another type of problem that is possibly present for gas chromatography has to do with the shape of the curve. As previously mentioned we want tall, skinny peaks that are more or less symmetrical and are sufficiently separated from one another as that is a hallmark of gas chromatography. There are two particular types of errors that have to do with the shape of the peak that are independent from those desirable characteristics. The first is called fronting or shouldering. The second is called peak tailing.

.jpg)

(Pictured above: an example of peak fronting)

They are opposites of one another. Wherein the fronting or shouldering is a characteristic where there is a noticeable curve that extends beyond a symmetrical starting point for the tall, skinny peak that eventually results in a correct peak shape that trails after the peak. Peak tailing is the opposite. This can be due to various types of issues such as in the case of peak tailing unexpected analyte interaction with solid support or stationary phase of the column (i.e., it sticks) or poor connections within the system or even a void in the column itself. Peak tailing can also be indicative of co-elution as demonstrated above. In the case of fronting or shouldering, it is most typically caused by an overload of the column.

Again it is the area under the peak that is measured in turns of quantification of the analyte of interest. Therefore, all of these basic chromatography problems of co-elution, elevated baseline error, baseline drift, peak tailing, shouldering, or fronting may and does result in a possibly false and inflated BAC result.

-Justin J. McShane, Esquire, Pennsylvania DUI Attorney

I am the highest rated DUI Attorney in PA as Rated by Avvo.com

You can follow me on Twitter, Facebook or Linkedin

Board Certified Criminal Trial Advocate

By the National Board of Trial Advocacy

A Pennsylvania Supreme Court Approved Agency

nulled says:

This definitely makes perfect sense!