Imagine. You go into your doctor’s office for a routine physical. As part of that routine physical, the doctor takes your blood. You come back two weeks later where the doctor delivers the single worst sentence you have ever heard in your life: “I’m sorry but you have cancer.” Then comes ever worse news from the doctor when the doctor says: “You have one possible chance at living. You have to undergo radical chemotherapy and a bone marrow transplant immediately.” You are shocked. You are young. You feel healthy. There is no family history of cancer.

Imagine. You go into your doctor’s office for a routine physical. As part of that routine physical, the doctor takes your blood. You come back two weeks later where the doctor delivers the single worst sentence you have ever heard in your life: “I’m sorry but you have cancer.” Then comes ever worse news from the doctor when the doctor says: “You have one possible chance at living. You have to undergo radical chemotherapy and a bone marrow transplant immediately.” You are shocked. You are young. You feel healthy. There is no family history of cancer.

After you recover as much as you can from the initial shock, you ask the doctor: “How do you know?” The doctor tells you that your blood sample that the doctor took two weeks ago was sent to the lab for routine testing using a test called a Complete Blood Count (CBC) examining your blood contents along with many other people from his practice. The doctor informs you that based upon the test run you have an abnormally high White Blood Cell Count (WBC) which is indicative of malignancy. You are floored. Still in disbelief, he shows you the result. As the doctor hands you the result, the doctor explains to you that at this lab, the lab runs a bunch of CBC tests right in a row using the same single testing instrument. That as a cost and time saving measure, the lab does not perform tests in-between each of his patient tests to make sure the device is clear thus making sure each test is only a report unique to that particular test and not due to the previous test.

While looking at the result, you note that your sample was labeled as sample 14 meaning that there were 13 others tested before yours. You ask the doctor about that. He pulls out his other reports and discovers that immediately before your test, there was a test done of his other patient who was unfortunately in Stage III or terminal end stage of cancer but who is still fighting with a superhigh WBC result. The doctor tells you about this other patient’s results and condition. The doctor gets a visible frown on his face. Despite all of this information, the doctor still tries to schedule the chemotherapy and the bone marrow transplant.

You have got to be thinking to yourself…no way. I would not undergo all of that based upon the way the tests were performed. That’s crazy.

Well, exactly that type of testing and evidence is what happens in Court every day and all day long in DUI and DUI Drug cases in the United States. It is reckless and shameful.

When you are accused of a crime that is almost entirely based on a numeric value, which is essentially what occurs in a prosecution based strictly on a reported Blood Alcohol Content result or a DUI Drugs case, we all want to be sure that the result is accurate, precise, repeatable, reliable, traceable, reproducible, robust and true being unique to that individual accused and that individual accused alone. However, as we discussed before “A large problem in Gas Chromatography: No uniform standard for GC run position or composition“, namely there is no order or reason as to what goes into the autosampler carousel and in what order the samples go into the autosampler.

This lack of standardization, even within the same lab and even from run to run made by the same technician, and especially with the nearly absent use of blanks is one of the fundamental flaws of Gas Chromatography for ETOH or drugs of abuse testing in America. In my considered opinion and in the general scientific community (as opposed to the law enforcement community), it is the single largest and most basic systemic problem with the way that Gas Chromatography is practiced in forensic testing today.

With this post, I will explain how the lack of using a blank before and after each unknown sample run invites well-deserved scientific scrutiny and rightly calls into question the conclusory reported and alleged result in every single case.

But first some background:

What is a blank?

Simply and generally, in analytical chemistry a blank is a sample that is prepared using the same methods that an unknown would be prepared within the run simply without the unknown added.

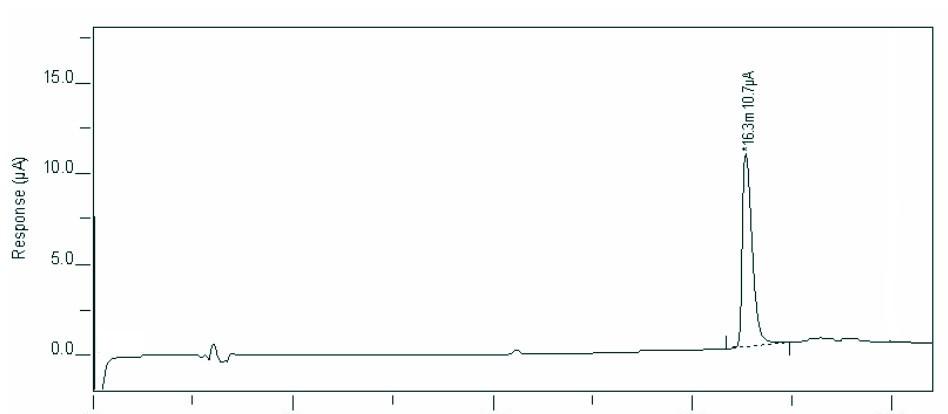

Ok, let’s translate that. In our case of assaying an accused’s blood which contains an unknown amount of analyte of interest (e.g., drugs of abuse or ETOH) is typically prepared by diluting the sample by adding a known amount of internal standard which is typically n-propanol when the unknown looked for is ETOH. [Blogger’s note: in the future a detailed post will be used to examine the use and potential problems when internal standards are used]. When a blank is created, the same exact amount of n-propanol that is added to the accused’s blood is added to a sample jar (in our case a headspace vial) but with no blood added. In simpler terms, it is a virgin sample with only n-propanol added. As a result, as there is only n-propanol, there should only be one peak on the chromatogram which corresponds to n-propanol. The lack of any other peaks is where the name of “blank” comes from in the analytical world.

(Pictured above: a blank with only n-propanol)

Why is this important?

In a phrase “carry-over effect” in another phrase an inaccurate inflated reported Blood Alcohol Content. Simply put, a false Blood Alcohol Content result. Think of it as contamination.

In analytical chemistry, carry-over effect can be thought in terms of pick up. When a carry-over event occurs the sample “picks up” the analytes of interest from a previous sample. A carryover effect is an effect that “carries over” from one experimental condition to another. It is a form of contamination from one sample to another.

Carry over in gas chromatography analysis can come from three typical sources: first, autodiluting [Blogger’s note: an entire future post will be dedicated to this concept]; second, injector contamination [Blogger’s note: an entire future post will be dedicated to this concept]; and third, remaining analyte on the column.

Whether direct injection or an autosampler is used, without a blank inserted before and after an unknown, then there is no way of scientifically knowing the alleged reported result is unique to that particular sample.

Until this very basic systemic flaw is solved, then it cannot be responsibly and scientifically asserted that the reported result is unique to the unknown analysis and not carried over from another analysis.

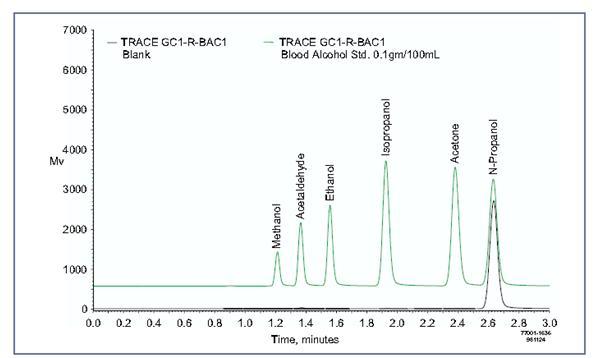

(Pictured above: an over lay of chromatograpms where in green there is the electrical signal as detected by a Flame Ionization detector when a Resolution Control Standard or Separation chromatogram is generated and in black is the blank run)

It is so easy to solve, yet no one seems to care. You just insert a blank. I guess the forensic science community doesn’t care because the result doesn’t affect them.

As an illustration, I draw your attention to a past post as a concrete example for this discussion. In “Highest reported BAC .708: I call Shenanigans“, we discussed an extremely high reported BAC result. Much like our cancer example, would you like to be the next test sample after that superhigh result? I would think not.

How about we start doing things in a scientifically responsible manner and run blanks in-between unknowns????

-Justin J. McShane, Esquire, Pennsylvania DUI Attorney

I am the highest rated DUI Attorney in PA as Rated by Avvo.com

You can follow me on Twitter, Facebook or Linkedin

Board Certified Criminal Trial Advocate

By the National Board of Trial Advocacy

A Pennsylvania Supreme Court Approved Agency

Glen Neeley says:

Justin McShane, I learned more from this article than spending 3 days in a seminar of scientists trying to explain this to my simple mind. This is an Outstanding closing argument. Thank you.